(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 158-59, 161-64)

The call-up of Company B and Company D reduced the number of men on campus; volunteers and the draft after Pearl Harbor took many more. By 1944, enrollment at A&M had dropped by 60 percent to only 170 students, most of whom were women. The joke of the day was that “all the boys on campus could be moved into one room.” In fact, the young men that year were housed in one wing—the shortest wing—of Cross Hall. The other men’s dorms were closed. Nelson and Caraway halls housed the women; Jackson Hall, not needed for students, housed unmarried female faculty. They found it easier to live in that dorm than in Magnolia due to difficulties in travel. Gasoline and tires were rationed, and even short trips were avoided. The A&M enrollment loss was so large that President [Charles A.] Overstreet felt it necessary to publicly deny in 1944 that the institution faced closure. Had the war not ended in 1945, however, the school might well have had to shut down.

In denying the rumor of closing, Overstreet declared that A&M finances were in the best condition since he had joined the institution in 1921. The war imposed hardship and sacrifice on the men and women who served in the armed forces and on their families, but in general, the domestic economy boomed, driven by wartime production. The war ended the depression and created full employment. Governmental revenues also surged. Since A&M received a fixed percentage of various taxes, the state appropriation grew 39 percent during the war that allowed Overstreet and the board of trustees to increase faculty salaries 27 percent and to join the recently established Arkansas Teacher Retirement System. A&M agreed to match the 4-percent salary contribution required of faculty who could retire at age sixty. Despite these additional expenditures, the efficient management of Overstreet increased the school’s cash reserves to $100,000 by war’s end. He hired fewer faculty and saved on energy and other costs by closing dorms.

• • • • • • • •

After 1941–42, there were fewer students and faculty and a corresponding reduction in the curriculum and in campus services. Courses with limited appeal such as advanced chemistry that [D. L.] Farley had taught were cancelled. The library was not open at night. The training school for student teaching closed. Arkansas faced a severe public school teacher shortage as teachers departed for well-paying wartime jobs; as a result, school consolidation increased. The Sanders school district whose children had attended the training school merged with the Magnolia school system. [Merrit] Alcorn arranged for A&M students to do practice teaching at McNeil. There were so few of them, however, he could take all of them in his car as he drove to work each day.

The curriculum expanded in physical education to toughen students who might be called to military service. In 1942–43, physical education classes met four times a week with an emphasis upon army-style calisthenics for both men and women. From 7 a.m. to 8 a.m. Monday through Thursday, the campus took on the appearance of basic training at a military base. First, young men, followed separately by young women, assembled in companies, each with a leader, for thirty minutes of vigorous exercise. Later an obstacle course was set up for the young men who also had to engage in wrestling to simulate hand-to-hand combat. All students took a required first aid course.

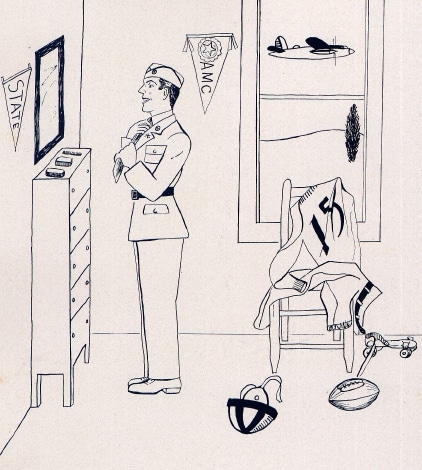

A&M did not have companies of soldiers enrolled for study like many four-year colleges did. The Navy Department approved the school only for a V-1 Navy Reserve course of study. This program required extra math and science classes in a two-year degree after which students who passed a special examination could transfer into a V-7 program elsewhere to earn a bachelor’s degree before becoming naval officers. The A&M V-1 program did not attract new students and enrolled young men who were already attending the school.

For a short time in 1942, small squadrons of men training for the Naval Air Corps came to A&M from outside Arkansas. The training cycles were for eight weeks per squadron to take the basic flight instruction that the CPTP course offered. In 1943, the Army Air Corps also sent men for flying lessons. As larger training centers were established elsewhere, the military discontinued training activities at A&M.

• • • • • • • •

Columbia County’s people endured, as did all Americans, the aggravation of wartime rationing. Gas, tires, and other consumer products including foods were available for purchase only with ration stamps that were presented to a merchant along with a payment when buying these products. Individuals were issued a limited number of ration stamps. Beer was in short supply in Magnolia, and the conflict afforded local citizens an opportunity to vote against alcohol sales. In a 1943 special election, they restored the area’s long-standing preference for prohibition that the end of national prohibition had briefly interrupted. Despite the smothering impact of prohibition and rationing, the area’s economy boomed, powered by wartime demands for the county’s products—oil, textiles, and agricultural crops.

Magnolia was thousands of miles from enemy forces and the war, but citizens in good humor practiced air-raid blackouts in 1942. Everyone supported the war and regularly bought war bonds to meet the county’s assigned quota. Citizens participated in scrap metal drives for war production. In a symbolic gesture, A&M contributed two steel ammunition caissons from the First World War that had stood in front of the armory since 1930. President Overstreet and Dean [E. E.] Graham headed countywide Red Cross and war relief fund drives that A&M students joined. Students humorously complained of going to breakfast in the dark middle of the night when daylight savings time began in February 1942. They eagerly volunteered to work in the Red Cross room in Jackson Hall that had been set aside for those making surgical pads and bandages for wounded soldiers. The girls of Caraway and Nelson halls competed with one another; and on one day in March 1943, together they made 1,315 bandages, helping to meet Columbia County’s quota of 30,000 for that year.

The war limited campus activities. May Day festivities continued on a limited scale, but the A&M Alumni Association did not hold its usual Former Students Day at year’s end or homecoming in the fall during the war. The Arkansas Intercollegiate Conference (AIC) cancelled all sports competition for the duration although intramural sports continued. Because coaches and physical education instructors left for the war, the bookstore manager, Henry Gladney, blind in one eye and unable to serve in the military, became the substitute director of intramural sports and physical education. Despite his best efforts, a Bray reporter concluded that the 1943 intramurals were “a complete and utter flop.” Stagecrafters continued to present plays, but few available males forced selection of productions with all-girl casts such as Nine Girls, a murder mystery involving vacationing sorority sisters.

By the end of the war, there were so few young men left on campus that women were in charge of almost all student organizations. The school’s first female president of the student council, Carolyn Tyndal from Nashville, served in 1944–45. With few men to date, the most romantic thing most young women could do was write to soldiers and go to the campus snack bar to play the jukebox music of Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey, and Benny Goodman. Young women complained about continuing the rule prohibiting coeds from downtown Magnolia on Saturday nights. It had been instituted in the late 1930s when oil field roughnecks cashed their paychecks and came to town for beer and fun. The rule was no longer needed, the women declared, now that the county was dry again.