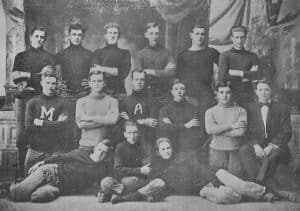

Shortly after Thanksgiving in 1912, young men from the football team of the Third District Agricultural School (TDAS) rode mules to Coach George Ruford Turrentine’s home north of the campus at Magnolia, Arkansas. In that year’s final game, they had played a scoreless tie game with Fordyce High School at TDAS on “Turkey Day,” November 28, and they wanted to talk over the season with the coach. It was not unusual for young men in the rural South to ride mules; as the animal used most often in Southern agriculture, they were easily available. In the school’s early years, football teams may have ridden mules occasionally to reach McNeil, five miles north of TDAS. It was there that they caught the Cotton Belt train to away games. There were only four automobiles in Columbia County in 1912 and no paved roads. Muddy roads in flooding weather conditions made travel difficult, even by wagon. Riding a mule was a more reliable means of transportation.

A few days after the Fordyce game, Coach Turrentine invited the players to dinner at his home, also located on the road to McNeil. As the riders dismounted in his yard, Turrentine walked onto his porch and shouted a greeting, “My Mule Riders!” This was the first known occasion when the name Muleriders was used for the football team. Over time, it became more than the team’s name. Among all the nation’s institutions of higher education, the name has been uniquely associated with the school established in 1909. Over the next century, only TDAS and its three successor institutions—Magnolia A&M College, Southern State College, and Southern Arkansas University—embraced Muleriders as a symbol for athletic teams, mascots, students, and alumni.

Coach Turrentine’s players enthusiastically embraced the name he had given them. Perhaps they saw its similarity to “Rough Riders,” the military heroes much on their minds because of the just-concluded 1912 presidential election. Former President Theodore Roosevelt had lost a bid to return to the White House, but the campaign had recalled his courage, his famed Rough Rider volunteers, and the story of their charge up San Juan Hill during the 1898 Spanish-American War. Some of Turrentine’s players, no doubt, were among the crowd of twenty-five thousand who gathered to see Roosevelt at the Arkansas State Fair at Hot Springs on October 10, 1910, when he visited with his old comrade, the Arkansas Rough Rider, Lieutenant John Greenway, a resident of that city. A Mulerider football team could not perform Rough Rider deeds of military valor, but it could act heroically in athletic battle.

As an avid reader of sports news, Turrentine may have thought of the name Muleriders. He knew that the famous Army-Navy rivalry, among the country’s most storied football competitions in those days, had as mascots, beginning in 1899, an Army mule and a Navy goat. As early as the Army-Navy Game of 1907, the New York Times described an Army mule with a rider pacing the sidelines, “He pawed and hee-hawed when Army chances looked bright, and his rider gave him his cue by tickling his muzzle.” Army had selected the mule as an appropriate mascot because of the animal’s “strength, persistence, heart, and resolve” in military operations, hauling guns, supplies, and ammunition since the Mexican War of the 1840s. The informal West Point cadet mule riders of early games would evolve into prestigious positions in the late twentieth century’s “Spirit Support Group” for Army’s football team, the Black Knights.

No mention of Rough Riders or Army mule riders was a part of an oral tradition among students that preserved the story of the Mulerider name’s origin. The name was not adopted officially until 1922–23 when the school yearbook became The Mulerider and the student newspaper The Bray. By that time, Coach Turrentine and his 1912 football players and the entire original faculty had left TDAS. Later Bray stories about the name’s origins varied in many details of time and place; the only common element in the stories was that early football teams rode mules to games.

The Mulerider as a symbol for the football team and mascot for TDAS, its students, and alumni was a fitting one. The mule was a crucial element of Southern agriculture. For most purposes, the mule was much preferred over the horse. It was more intelligent, more stubborn, healthier, stronger, and more sure-footed. As a result, a mule was more expensive to buy than the average horse. In addition to his role as father of his country, George Washington was also the father of his country’s mule business. He used the gift of a large jack (male donkey) from the King of Spain to breed mares to produce hybrid mules not only for Mount Vernon but also for other plantations across the South when he sent Royal Gift on tour. Despite this historic origin, the mule had a lowly status in Southern culture. The mule was used in the hard work of growing cotton that was the wealth of the South. But this was the work of slaves before the Civil War and, later, of tenant farmers. Only poor farmers were likely to ride mules rather than horses. The horse was associated with genteel leisure pursuits like buggy rides and horse races. The choice of the symbol of Muleriders represented both an assertion of superiority and of status inversion. TDAS and its successors held a lesser rank in the hierarchy of educational institutions and provided educational opportunities primarily for the sons and daughters of farmers and workers of Southwest Arkansas who, through hard work, could rise to the top.

Muleriders remained the symbol of the school in its subsequent evolution as a junior college, a senior college, and a university because of the icon’s uniqueness, authenticity, and connections to the region’s history. The mule had deep roots in the everyday lives of TDAS students and their families. Connections to that past continued at Southern Arkansas University (SAU). Far fewer students in later decades majored in agriculture, but the working campus farm remained an important feature of the school. For almost half a century, the school has had a rodeo team and joined the National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association in 1972. It was one of only one hundred four-year schools in the United States to sponsor rodeos. Its riders were a link to the Rough Riders, many of whom were Western cowboys. For more than sixty years, the logo of the Muleriders, first appearing on the masthead of the Bray, has been a graphic of a rider in Western garb atop a wildly bucking mule. A bronze sculpture of the Mule Rider created by Jason Scull has a prominent place at SAU’s Donald W. Reynolds Campus and Community Center. At each home football game, a Mule Rider parades the sidelines to support the team. One aspect of Muleriders has changed. Over the course of the symbol’s hundred-year history, the original two-word name was changed to the compound Muleriders to accommodate evolving style usages.

For more information about various mule mascots and riders during Southern Arkansas University’s first century, click here:

History of the Mulerider Name and Mascot 1920-1950

History of the Mulerider Name and Mascot 1950-1976

History of the Mulerider Name and Mascot 1976- 2009

Text excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009 (2009), pp. 13-17. Photos provided by SAU Archives.