(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 153-58, 164-65)

The day that Japanese warplanes bombed American naval forces at Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands was Virgil Bell’s most unforgettable memory of his years at Magnolia A&M. At the fiftieth reunion of his class, he recalled the moment, “Dec. 7, 1941, in gym listening to account of Pearl Harbor.” When the White House released news of the attack that took place early Sunday morning Honolulu time, many Americans heard of it when radio announcers interrupted regular broadcasts. After the first reports, a radio was hurriedly set up in the A&M armory so stunned students could gather to hear news reports.

Three years earlier during the Munich crisis of 1938, CBS News had first aired reports direct from European capitals. After German leader Adolf Hitler sent his Nazi forces into Poland in 1939 and began the Second World War, Americans grew accustomed afterward to hearing Edward R. Murrow and William L. Shirer report “live” from London and Berlin. A&M listeners on December 7 heard broadcasts from Honolulu, Manila, Singapore, London, New York, and Washington. Reports were fragmentary due to chaotic ongoing events and to governmental decisions not to reveal the full extent of the damage at Pearl Harbor.

Faculty and students nonetheless knew that December 7 was a major turning point in their lives and for the nation. America could no longer stay out of the war, and young men, perhaps friends at A&M, would die on far-flung battlefields. Lives back home would be disrupted, and their college’s future was uncertain. The conflict’s impact on A&M was substantial. After 1943, the war seemed to threaten the institution’s existence. But after several difficult years, the war’s aftermath catapulted the school into the ranks of four-year colleges.

Listening to the radio in the armory made distant events at Pearl Harbor seem immediate and close. In mid-January 1942, news came that brought the attack even closer to A&M. Official notification from the War Department arrived in Magnolia reporting that Marine Private Carl E. Webb Jr. had died aboard the USS Arizona, a battleship that Japanese attackers had sunk. Webb had been an A&M student in 1939–40. His parents owned and operated the Webb Hotel near the Magnolia town square.

• • • • • • • •

World events touched the college with increasing frequency after 1939. A&M students and faculty were often called upon to contribute money for war refugees. A&M’s band solicited funds for Finnish Relief when the Soviet Union attacked Finland. Faculty members held a golf tournament at Magnolia’s first country club located north of the campus to support British War Relief.

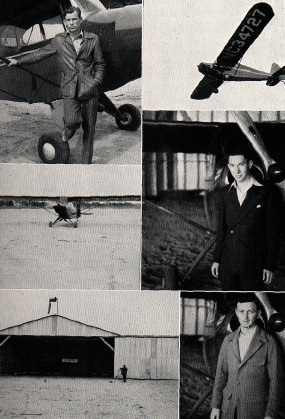

When the U.S. government began national defense preparations, the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) established a Civilian Pilots Training Program (CPTP) in the nation’s colleges. Its purpose was both civilian and military; more civilian pilots would expand the pool of potential combat fliers. Magnolia Chamber of Commerce President Archie Monroe cooperated with A&M to secure a CPTP. The CAA would not give approval without an adequate airfield so the chamber hastily had one built south of Calhoun. The college engaged local pilot R. B. “Burley” McCulloch as flight instructor. Science instructor D. L. Farley taught the necessary ground courses including meteorology, navigation, and aviation regulations. Initially, women as well as men were accepted into CPTP. Maxine Wright of Murfreesboro graduated with A&M’s first CPTP class. Later, however, the government excluded women since they were not permitted to fly in combat. By December 1941, A&M’s CPT Program had turned out forty-five novice pilots.

• • • • • • • •

When Congress enacted the Selective Training and Service Act in September 1940 (the nation’s first peacetime draft) A&M students registered. Some men did not wait to be drafted and quickly enlisted. So strong, however, were public opinion and the congressional mood against U.S. entry into another war that the conscription law was enacted for only one year. It was renewed a year later by a margin of one vote in Congress. Young men across the country felt it was their duty to serve, and after the war began, some twelve million wore their country’s uniform.

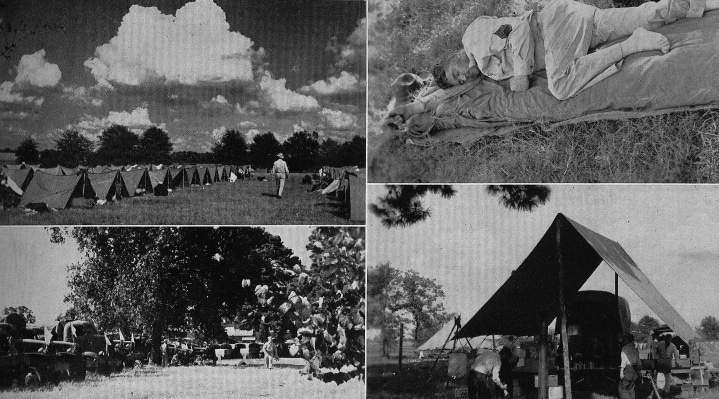

A small number—twelve thousand—refused all military service on religious grounds and became conscientious objectors (COs). The Selective Service administration permitted the “peace churches,” the Quakers, the Brethren, and the Mennonites, to establish camps for COs where they could engage in alternative national service such as soil conservation, forest-fire fighting, and similar work. Camp No. 7 was located in quarters north of the A&M campus that formerly had been used by the Civilian Conservation Corps.

A&M gave these COs a respectful reception despite the deep patriotic emotions stirred by the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor. Many of the COs were well educated and spoke to groups on campus in the fall of 1941. Among them was a young philosopher, Morris T. Keeton, a recent Harvard Ph.D. who would later serve as president of Antioch College. He lectured A&M students on what he claimed were President Roosevelt’s attempts to maneuver the United States into war, a criticism often voiced in those days by isolationists. During the war, some Columbia County citizens expressed hostility toward the COs. A&M students and faculty, however, apparently bore them little ill will. The Mulerider basketball team played one of its last games of the 1942 season against a Camp No. 7 squad, winning a close game over the COs by one point, 33–32. When a tornado destroyed the CO camp in April 1944, A&M’s infirmary received the injured, and the other men lived in McCrary Hall until they were dispersed to camps across the country.

• • • • • • • •

Arkansas National Guard Companies B and D housed at the armory and composed largely of A&M students trained more vigorously once war in Europe began. Captains Ves Godley [, an agriculture instructor,] and engineering and manual arts instructor Edgar L. Watson commanded the units that made long marches and attended weekend encampments. Throughout 1940, the units received indications that they might be called soon to active duty. Captain Watson, a veteran of the First World War, too old and in ill health, retired. Agriculture instructor Lieutenant Truman O. Garinger was promoted from lieutenant to captain to replace him. Godley, who had served in the earlier war as an underage enlistee in the navy, remained with his young men. The companies left for a year’s active duty with the regular army on January 10, 1941, and were stationed at Yakutat, Alaska. Most men would not return home until 1945. The units did not see combat although Godley and some others were at the Dutch Harbor hospital when the Japanese shelled and bombed that port. Other men in the guard companies left to volunteer for service with other units elsewhere, and some of them saw action in Europe and in the Pacific.

• • • • • • • •

News reports and letters of former A&M students in the military arrived from time to time. Juanita Lane the former Bray editor who had joined the Navy WAVES had quickly sent the student paper an account of her experiences. Few young men did so. Not until the war’s end would the full extent of their service become known. Registrar Matsye Gantt carefully compiled a record. She issued an “A&M College Service Honor Roll” showing that 908 men, 18 women, and 12 faculty (9 men and 3 women) had worn their country’s uniforms. The ultimate sacrifice had been made by 48 men, half of whom had completed A&M degrees.

From fragmentary reports, those who remained at A&M learned of former fellow students fighting, some dying, in battles in Bougainville, Tarawa, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, the Philippines, North Africa, and France and of others flying missions over China, Italy, and Germany. After the war, a number of dramatic accounts of combat experiences were recorded. Navy flier Doy Duncan, who briefly attended A&M in 1942, when shot down at the Battle of Leyte Gulf survived in the sea two and one-half days without water before being rescued by Filipino guerillas. Decades later, the Netherlands Prince Bernhard pinned the Dutch Resistance Cross on the shoulder of Charles L. Allen, class of 1943. He had been part of a secret OSS (Office of Strategic Services) mission in the Netherlands—the Melanie mission—an exploit that had gone unrecognized when Allen quietly returned home and became a minister and rural mail carrier at Camden, Arkansas.

Some A&M veterans of the Second World War remained in the armed forces and rose to high positions. These officers included two navy admirals, E. T. “Tommy” Westfall and Joe Williams Jr.; two navy captains, William Madison Gordon and Curtis T. Youngblood; two army colonels, West Point graduates Kenneth McRae Lemley and William Glenn Watson, who had grown up on campus, the son of Edgar L. Watson; and several air force officers including Colonels Perry Ford and Orman “Gene” E. Hicks. The officer who attained the highest rank was Magnolia native and 1936 A&M graduate Horace M. Wade who became a lieutenant general and vice chief of staff of the air force.