(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 165-70)

Veterans who came back after the war transformed Magnolia A&M and the nation’s other colleges. Within months of the war’s end in August 1945, thousands of ex-servicemen and women flooded campuses, and millions more soon followed. The GI Bill®—officially the Servicemens’ Readjustment Act of 1944—provided this educational opportunity. Veterans received funds to pay college fees and living expenses. The GI Bill® provided social and economic mobility for a generation. It made America a fairer society in which family background and income counted for less and ability and effort for more. The GI Bill® gave much support to the Magnolia institution’s long-standing mission of opportunity for students who could not otherwise go to school.

Only eight veterans including one woman, an ex–Navy WAVE, enrolled at A&M in September 1945; but by the 1946 fall semester, there were more than 300 among the 562 full-time students. Postwar enrollment peaked at 621 students in the 1949 fall semester. Administrators had to scramble to accommodate such large increases in such a short time.

A new president had to handle the problems that this growth created. After President [Charles A.] Overstreet resigned in June 1945 due to ill health, he retired to his farm north of the college. The board named Dean [E. E.] Graham acting president while it searched for a permanent head. Graham over the next four months acted essentially as a “caretaker” administrator. He made no major changes; he did hire two or three new faculty as well as a new business manager, John Ed Cleaver, who, like his long-serving predecessor, Walter Herndon, would remain at the school for two decades. Graham also made inquiries about surplus materials that the college could acquire—housing and tools—as the U.S. government began its wartime demobilization.

The new president—Colonel Charles S. Wilkins—assumed his duties on November 1, 1945. Although he soon completed a doctorate in agricultural economics from Texas A&M University, Colonel Wilkins would continue to be addressed by his military rank. A graduate of North Texas State at Denton, Texas, he had coached football at Beaumont before earning a master’s degree at the University of Texas in 1929. He then joined the faculty at John Tarleton Agricultural College in Stephenville, Texas. There he became dean of students and registrar. In September 1945, he returned home from France after five years in the army and six weeks later moved with his wife and three children into the Magnolia A&M president’s home.

• • • • • • • •

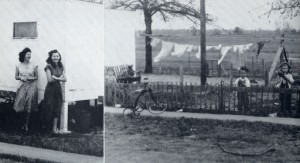

Wilkins continued Graham’s inquiries about war surplus house trailers for returning veterans. He and Graham anticipated the new need to house couples since many veterans were married. A&M had never provided such accommodations; in fact, few married students had ever enrolled up to that time. By the 1946 fall semester, the school had made a good start in establishing a residential area for families. Students quickly named it Wilkinsville. It was located on the northern edge of campus (the later site of Honors and Greene halls).

Wilkinsville was largely a trailer park. Most of the trailers were designed to accommodate two people. Each had a bed, cookstove, sink, and refrigerator but no toilet or shower stall. Communal facilities were built for those purposes and a washhouse to clean clothes. Despite its hardships, Wilkinsville became a thriving community, and soon a small playground was added for the “tots” of growing families. Rent was inexpensive at $20 a month with no additional charge for water or electricity. A small number of apartments were added (along the western edge of the area that later became the baseball field). So many single veterans came to A&M that the dormitories quickly filled. As in earlier periods of heavy enrollment, three or four persons were sometimes placed in a room meant to house two. Additional space was added with war surplus “hutments” that were set up in the area behind McCrary Hall and next to the armory. These huts could accommodate up to four men.

Besides creating a demand for more housing, veterans changed the campus in many other ways. The veterans were mostly single men, and males soon outnumbered females by three to one, substantially more than the two to one ratio that had existed for most of the school’s prewar history. Soon, women once again were rarely elected to head student organizations. Mamie Jo Taylor served during the 1945 fall semester as student council president, but when she left at midyear, Dave Townsend won a special election. In May, Sess Hensley defeated Winnie Dodson, captain of the popular women’s basketball team, to become the 1946–47 president. It would be twenty years before another woman was elected president of the student body. This return to traditional male-female leadership roles was not peculiar to A&M. Throughout the United States in the postwar years, civic and religious institutions encouraged women to resume traditional roles as wives and mothers. Their wartime participation in many activities previously considered the domain of men alone was considered an aberration.

Veteran enrollment also affected A&M academics. Most veterans were serious, hard-working students, and they established record-setting percentages in the numbers of students making the dean’s academic honor roll. Ex-GIs typically focused on “practical” courses of study leading directly to employment. As a result, majors in engineering, business, and agriculture skyrocketed, outstripping the favored choice of the 1930s—arts and sciences—by wide margins. Among curriculum changes responding to veteran interests was the addition of petroleum engineering, an obvious career choice in oil-rich South Arkansas. Class absence rules were relaxed. So long as a B average was maintained up to the time of the final exam, “cuts” of classes were not counted against a student. Students who failed to maintain the B, however, faced a mandatory comprehensive exam at semester’s end to remove any penalties resulting from excessive “cuts.”

The presence of veterans inevitably led to relaxation of other rules. Dean of Men Sage McLean strictly enforced rules, but soon men were more or less free to come and go as they pleased while living in the dorms. Destruction of property and physical violence, of course, were prohibited as were drinking or creating disturbances. “Dorm Mothers,” usually widowed women, kept order in several halls. Mrs. Nora “Ma” Adams took care of her “boys” in Cross Hall for fifteen years, an era during which this dorm was reserved for athletes.

Firmer rules for young women would remain in place for twenty-five more years. Signing in and out of the dorm, returning from a date by 10:30 p.m. (later extended an hour or so), and locking the dorm doors at night—all continued. Dress codes for women required wearing a dress or skirt much of the time. Many alumni from that era can recall the “strange” sight of a coed wearing a required raincoat when the sun was high in the sky. Underneath she had on gym shorts and was on the way from her dorm room to a physical education class.