(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 57-59)

Supervision and discipline of students at TDAS was not unique. All educational institutions of the era, and for decades to come, dealt with students according to the tradition of in loco parentis (in place of parents), a policy that actual parents thoroughly approved. For a time, students were required to attend one of the five churches in Magnolia. This practice was abandoned, however, perhaps in deference to freedom of conscience; but local ministers still took turns coming to campus to speak at some of the required daily assemblies. For several years, girls had to follow a dress code prohibiting expensive apparel. This rule was probably aimed at growing numbers of day students, the children of more prosperous Magnolia families who came from home each morning to the campus.

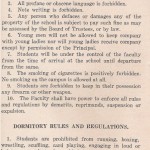

Early catalogs contained long lists of both prohibited and required acts. Students were to obtain permission of the principal to leave campus, attend parties, write notes to each other, or to “keep company” with the opposite sex. Students were forbidden to smoke, drink alcohol, use foul language, or play cards. In the dorms, running, boxing, wrestling, or boisterous conduct were prohibited. Beds had to be made, slop carried out, and rooms swept clean each day by 7:30 a.m. Students not in class or at work during school hours were required to attend the study hall. Students were to remain in their rooms preparing the next day’s lessons from the first bell at 6:45 p.m. until the bell rang later for bedtime. Mrs. Ona Westbrook Adkins, a member of the 1911–12 class, later recalled, “Boys? We couldn’t even look at them! Dance? Why, the only way we girls danced was into our rooms at night!” Mrs. Jackson would “corral us into our rooms, because the rules were that we had to be in bed by nine o’clock with the lights out.”

Sage McLean, Chemistry Teacher, 1924-1960; Mulerider Coach, 1924-36; Dean of Men, 1946-1960 (Click photo to enlarge)

Faculty and staff, especially the kindhearted Mrs. Laura Jackson, probably did not rigidly enforce these rules. For serious infractions, the usual penalty was “walking the post.” It was adapted from a military punishment that involved walking back and forth from point to point an exhausting number of times. Harper Sanders, the former Clemson military cadet captain, may have instituted this practice when he served as principal. Intolerable misbehavior resulted in prompt expulsion, the fate of one young man in the spring of 1911 and several more over the years. Usually, the matter was less serious and the penalty less severe, like one recorded in the 1915–16 yearbook’s calendar: “Dec. 8—Boys go the picture show. Dec. 9—Result: Walking the post. Magnolia’s first silent movie theater, the Majestic, charged only five cents admission to view a two-reel comedy of Charlie Chaplin, which no doubt had proven irresistible. Smoking was impossible to stop, for students found an ingenious method of hiding the evidence. A coach and science teacher, Sage McLean, recalled that when he first came to campus in 1924, the flues of woodstoves used in the dorms before they had steam heat were just then being removed during a remodeling. Found inside the flues, filled to the brim, were cigarette butts and lots of litter.

Undoubtedly, young men and women resented efforts to keep them separated. There was initial segregation by gender at all assemblies of any kind. At required chapel held each morning before classes, seating was assigned, men on one side, women on the other, and roll was taken. This same practice took place at meals. Soon, however, domestic science teachers, who supervised the dining hall, decided to use meals to teach table manners and social graces. Males and females had assigned places at tables seating eight. One girl at the table brought the food from the kitchen and served it. After eating had ended, all diners were supposed to remain seated, engaged in quiet conversation until a bell permitted them to leave. Every few weeks, teachers moved students so that they would become more widely acquainted. This serving arrangement (but not the bell system or involuntary assignment of seats) continued for many years. Cafeteria serving lines were not used until the mid-1930s.

To reward good behavior, principals, at irregular intervals and on special occasions, would announce, “Rules were off.” When the “rules are suspended,” explained the 1915 yearbook, “every boy gets him a girl.” Daytime “dates” were allowed for walks about campus. Chaperoned groups could go off campus.