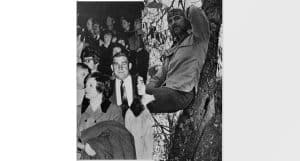

A merged photo of two SSC students in 1970—one in a tie at a football game, the other with a beard in a tree (Click photo to enlarge)

(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 256-260, 270)

College students throughout the country in the 1960s revolted against authority and tradition in many ways, including wearing long hair and sloppy dress, using marijuana and other drugs, and demonstrating and protesting. Even ordinarily conventional students agitated against the restrictive in loco parentis rules of higher education that governed student behavior. Only a tiny minority of those in rebellion, however, were true radicals who wish to overthrow “the system.”

Arkansas students, unlike those elsewhere, were largely quiescent and SSC students especially so. There were only a few brief sit-ins and occupations of administrative offices and antiwar demonstrations at other Arkansas campuses. The state’s higher education institutions, however, had numerous controversies involving student rights and the academic freedom of faculty. As a result, Arkansas had more schools under censure of the American Association of University Professors than any other state in the country from 1962 to 1976.

At SSC, student activism began in 1960 when supporters of John F. Kennedy formed a Young Democrats Club (YD) and went to a Texarkana election rally where he spoke. Some of these YDs staged a mass walkout of their club on April 24, 1962, to protest the “Old Guard and Governor Faubus.” That very night, they moved to a new location and formed a Young Republicans Club (YR), announcing support for Winthrop Rockefeller as governor. For the rest of the decade YDs and YRs at SSC fiercely competed for student support. On more than one occasion before Governor Orval Faubus left office, his aides called Dr. [Imon E.] Bruce to complain about SSC’s YDs.

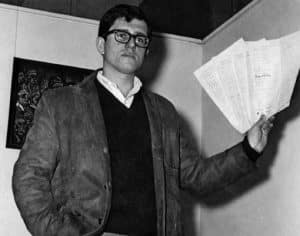

Among the YDs resigning in 1962 was freshman student journalist Bob Lancaster of Sheridan. He was also at the time writing letters to the Arkansas Gazette under a pen name, “Auspice, Southern State College,” harshly attacking Governor Faubus. Only six weeks after Lancaster became Bray editor in the 1962 fall semester, Dr. Bruce fired him, apparently for running cartoons that offended some religious groups and because the governor’s office, which monitored the state’s college campuses, had complained about “Auspice’s” letters. Lancaster left college without a degree but became a renowned Arkansas newspaper columnist and writer. A decade after leaving SSC, he was among the youngest recipients of a Nieman Fellowship for journalists for a year’s independent study at Harvard University in 1972. His fictionalized autobiography, Going Down for Gum Wrappers (1985) unflatteringly depicted “Magnolia’s Frog Level U” administrators who “had a dromedary look and air about them.” Twenty years later he had forgiven Dr. Bruce, and mellower memories led him to favorably compare the impact of SSC with that of Harvard on his intellectual development although at different levels of sophistication.

Protests over campus rules governing student life grew more frequent at SSC in the 1960s, increasing when long hair and dress that administrators thought disreputable appeared. One anonymous student wrote to the Bray in 1965 denouncing campus restrictions and asked, rhetorically, “Will it come to a minor Berkeley? I hope so.” Berkeley referred to the Free Speech Movement in 1964 at the University of California that marked the beginning of campus rebellion in 1960s America. That incident arose over students’ rights to set up tables on campus for civil rights recruitment and fund-raising. When blocked, students used the nonviolent but disruptive tactics of the civil rights movement against segregation. The dispute led to a student sit-in of administrative offices and mass arrests of the protestors before Berkeley finally gave in. SSC’s protests against campus dress rules were pale by comparison.

At SSC, petitions for changes in rules circulated in November 1966 and gained the signature of 950 students. The Student Senate endorsed the petition, and when the administration ignored it, the senate in February 1967 voted for a “boycott” of the cafeteria until the Sunday noon dress code—requiring men to wear a coat and tie and women “dressy dresses and heels” to be served a meal—was abandoned. The boycott was called off after Dr. Bruce appeared personally to tell senators firmly that the dress code was “a closed matter.” The president did agree that the senate could work on proposed rules changes.

Sharon Smith, first female president of student government association (SGA) presides over student senate in 1968-69 (Click photo to enlarge)

Six weeks later, Sharon Smith of El Dorado ran for SGA president on a seventeen-point platform calling for specific rules changes and for a “Student Bill of Rights.” In the largest ever election turnout—over 1,200 student voters—Smith won, the first woman to become student body president in a contested campaign. Paul Hoover of McNeil followed Smith as president in 1968 with a similar platform, calling in addition for a student representative on the board of trustees.

Over the next several years, most of the rules opposed by students were eliminated. Student agitation had its impact, but more important were the progressive attitudes of younger student affairs staff led by Dr. Donald Haefner, various deans of men, and the dean of women, Pat Weaver. Judicial decisions also changed the landscape. Court rulings recognizing student rights and liberalizing examples set by colleges across the nation came into play in Magnolia. There were also pressures from SSC’s neighboring colleges that relaxed their rules. SSC followed suit in the competition for students as most Arkansas schools faced declining enrollments beginning in 1969.

In one noteworthy instance—giving junior and senior honor women with high grades their own keys and no curfew hours in a special dorm—SSC was ahead of the institutional curve. In 1968, Dean Weaver was largely responsible for this innovative, and, for SSC, daring change. It was the result of a greater trust in coed maturity and practical realities that included a larger enrollment than the three women’s dorms—Bussey, Harrod, and Nelson—could accommodate and the serendipitous availability of the men’s athletic dorm. Cross Hall became vacant when athletes were concentrated in the much larger Greene Hall.

The Vietnam War was the issue that most agitated the nations’ campuses. College students in academic good standing were exempt from the military draft that was, by the 1965 fall semester, taking thirty thousand young men every month. Nonetheless, antiwar sentiment in colleges surged. Professors and students led all night teach-ins criticizing the war. SSC’s YDs in October 1965 sponsored a short teach-in by professors, none of whom took a strong antiwar position. Afterward on Armistice Day, November 11, the YDs manned a table in the student union gathering signatures for a petition to support the troops and passing out badges for hundreds of students and faculty to wear. Each badge bore a statement backing the soldiers, if not the war itself: “We support our generation of G.I.s in Vietnam.”

Dr. Bruce was away from campus, but he had two deans try to stop this activity, fearing a precedent that might lead to antiwar petitioning. The deans relented, however, when YD leaders, who had already provided publicity to area newspapers, warned that journalists might well portray censorship as “unpatriotic.” The only antiwar demonstration held at SSC took place on May 12, 1970, when some two hundred students and faculty marched around campus to demonstrate against the Ohio National Guardsmen’s shooting of student protestors at Kent State University a few days earlier. Similar marches of solidarity were held at almost every campus in the United States. No one in SSC’s administration tried to block the demonstration.

An unknown number of SSC graduates and former students served in Vietnam. Careful records had been kept of A&M students and faculty who had fought in the Second World War. Unfortunately, there were no such records for either the Korean or Vietnam wars. Occasional mention of soldiers and veterans appeared in campus publications. Vietnam veterans did form a campus club in the 1970s. Two SSC men’s names are inscribed on the Vietnam Memorial Wall. Navy Lieutenant Ed David Taylor, class of 1960, was shot down over North Vietnam while piloting an A-1H Skyraider on August 26, 1965. His remains were recovered and brought home to the United States in 2001. Former student Michael Rasberry was killed in ground action in Vietnam on April 4, 1968. Unknown SSC students’ names may well be on the wall.

· · · · · · · ·

SGA’s advocacy of student evaluations was one example of its continued assertiveness in the early 1970s. The senate repeatedly asked for representation on the board of trustees, the right of eighteen-to-twenty-one-year-old students to live off campus, and open visitation rights for men and women in each other’s dorms. On some matters, student demands were impossible to meet. On the issue of dorm visitations, Dr. Bruce and the board of trustees appeared indecisive. Students complained about the administration’s “run-around.” In the end, students who wanted all dorms to be opened had to settle at first for visitation in only two dorms on Friday evenings and Sunday afternoons. The administration had to balance many competing interests and needs. Most coeds did not want men wandering around their hallways, and many parents, and local citizens were outraged at the thought.

Even on the issue of fraternities, Dr. Bruce and many faculty stood in opposition as long as they could. Dr. Bruce said he rejected a student body vote in March 1968 in favor of fraternities because of insufficient participation. An unusually effective SGA president, Ed Trice, in 1969–70 carefully built support step-by-step. First, a senate committee conducted an investigation showing that SSC was almost the only school in the state without fraternities. Next, a petition drive was conducted door-to-door in each dorm. When not enough women signed up, sororities were dropped from the proposal. Then with faculty allies, approval of fraternities was obtained from the Student Affairs and the Faculty Affairs committees. Finally, at a general faculty meeting, there was a close but positive vote, 42–39. A month later, the board of trustees gave approval.