(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 284-287)

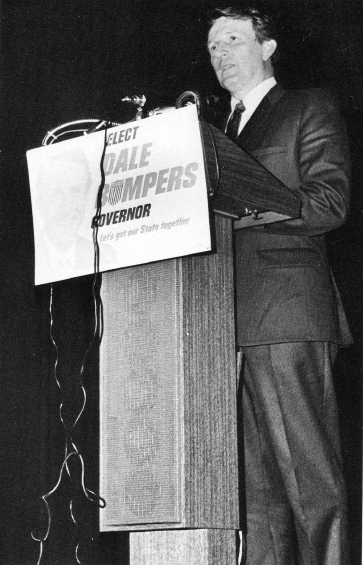

Supporters of SSC and the other small state colleges worried that some legislators wanted to merge all state colleges into one university system. Grateful for the new taxes, they were not as resistant to Act 38 (1971) as they might have otherwise been. With this law, Governor [Dale] Bumpers achieved a major government reorganization that included turning CCHEF into the Department of Higher Education (DHE) as part of his new cabinet. DHE had slightly increased powers to review programs as well as coordinate budgets. The legislature directed DHE to conduct role and scope studies of each institution and report to the 1973 session. A program review recommended deletion of ten SSC programs. Due to Arkansas’s constitutional Amendment 33, the autonomy of college boards remained an obstacle to DHE’s powers. SSC’s board rejected DHE’s recommendations and eliminated only two programs—French and industrial distributive education.

Governor Bumpers’s financial largesse to the state colleges and universities came at an additional cost, one that Dr. [Imon E.] Bruce vigorously opposed. That was the expansion of the state’s community junior college system. Implementation of Amendment 52 of 1964 providing for community junior colleges had placed primary financial responsibility for these institutions upon local communities. In almost ten years, only Sebastian and Phillips counties had voted property tax millage rates to support community colleges. Arkansas’s nearest neighbors had funded comprehensive systems; Missouri, for example, had twenty-two community colleges. Oklahoma, Texas, and Mississippi had as many or more than Missouri.

Governor Bumpers endorsed a 1972 report of the State Advisory Commission on Community Junior Colleges for more institutions and declared he would present “an ambitious proposal.” Acts 103 and 678 (1973) shifted to the state the primary responsibility for operating costs of community colleges after local taxpayers built such institutions. At a time when Arkansas still did not adequately fund its four-year schools, critics opposed diverting money to more two-year colleges. The Arkansas Gazette repeatedly characterized it as “Bumpers’ Folly.” Making this same argument, Dr. Bruce apparently helped persuade every South Arkansas legislator in counties that SSC served to vote no, but the bills easily passed. To head off a movement for community colleges in Southwest Arkansas, Dr. Bruce announced that SSC would increase extension classes in El Dorado, Camden, and Hope, cooperating with the state vocational-technical schools in those cities to meet local educational needs. Except for Dr. Bruce and the Southwest Arkansas legislator’s opposition to more community colleges, higher education was largely mute probably because Governor Bumpers provided a remarkable 46 percent increase, overall, for higher education. It was the fifth highest increase in the United States at the time. SSC’s share of the appropriation was a generous one and included a welcomed $2 million for Dr. Bruce’s construction projects.

Dr. Bruce’s continued opposition to a community college in El Dorado was probably the final issue that led to his forced retirement. He explained to alumni at the 1975 homecoming luncheon that in 1974 “it became apparent that the majority of the Board thought that someone else would do a better job” and that he should retire at age sixty-five. Supporters of a community college in El Dorado organized soon after Governor Bumpers’s plan was passed. Several competing needs for increased local taxes in El Dorado, however, stood in the way and would enable opponents to make a case against building a college. Dr. Bruce publicly argued that El Dorado did not need a school. SSC extension classes could offer the same services at less expense.

A political solution to get around the opposition emerged when David Pryor was elected governor in November 1974. As the 1975 legislature opened, a coalition of South Arkansas legislators acted quickly to push through a bill for two branches of SSC: (1) a new community college at El Dorado and (2) an existing vocational-technical school, the Southwest Institute, at East Camden. The new governor signed the controversial Act 171 on February 14, 1975. Opponents criticized the governor’s “Valentine” for the “home folks” (Pryor was a Camden native). It created, the Arkansas Gazette declared, an institution of questionable origin, born “without benefit of clergy,” i.e., without a popular election to increase local taxes like the state’s other six two-year colleges. Later that year El Dorado did hold a millage election to build public school facilities, which permitted leasing for $10 a year an old school building for the SSC branch. Governor Pryor was defensive about Act 171 because he had previously condemned “the burgeoning” of two-year colleges and vo-tech schools, vetoed bills establishing two-year branches for Henderson State at Mena and for Arkansas State in Crittenden County, and pursued a fiscal posture of “austerity and great caution” limiting higher education funding.

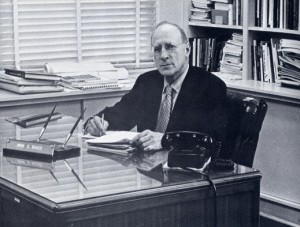

As the legislature was about to establish branches for SSC, Dr. Bruce announced that he would step down as president in 1976. He did so at the board meeting when an El Dorado delegation won SSC’s trustees’ endorsement of their branch plans. Fortunately, Dr. Bruce’s concerns about community colleges, perhaps reasonable at the time, were not born out in the future development of Arkansas’s higher education system. Dr. Bruce finished his last eighteen months at SSC as he had the previous fifteen years, working as hard as he could. Despite the difficulties that his approach to managing SSC occasionally caused, he had accomplished much. A 1975 study by two Indiana University professors of higher education judged him an “outstanding president.” Even those who criticized him did not doubt his selfless devotion to his alma mater. As its president from 1959 to 1976, he took no vacation time. His salary increased more slowly than his faculty’s. His office remained a plain room, barely furnished. He spent nothing on the president’s campus home. The Indiana University professors ended their analysis of Dr. Bruce with this well-deserved accolade: He “had not suffered from the delusion of grandeur that afflicted such a large proportion of college and university presidents.”