(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 222-224)

In 1957 and 1961, a few students participated in an unusual extracurricular opportunity. George E. Fay, a young anthropologist and sociology instructor, led students on trips to Mexico. Fay frequently conducted archeological excavations in the state of Sonora, Mexico, and students benefited from these cultural and educational experiences. Fay had a quirky but jovial and approachable personality that attracted a student following. He kept voodoo dolls at his office and challenged his classes by presenting alternatives to the usual conventions from his knowledge of other societies.

Students admired many other teachers. Alumni often remember three in particular whose enthusiasm for their subject stimulated undergraduates. Inez Couch was then in her fourth decade of teaching English at the institution. A white-haired lady who looked like an aging grandmother, she delighted students when she recounted the risqué misdeeds of the old English kings and queens, but she was “uncompromising” in expecting the greatest effort of students.

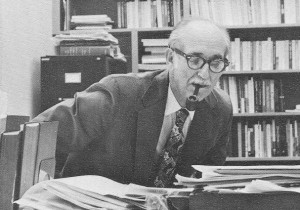

Dr. George Sixbey, a Yale Ph.D., headed the English faculty in the 1960s. His student, Dan Ford, who later became his colleague, remembered Dr. Sixbey as “a big man with a mustache, who constantly smoked a pipe. He wore tweed or corduroy jackets with leather patches on the elbows. When he taught he spoke from the text and from the heart, bringing literature to life” and “having wonderful fun as a scholar and teacher.”

Dr. Robert Walz looked older than his age. He had graduated from Magnolia A&M in 1939 and after the war earned a Ph.D. in American history at the University of Texas. He had many fans among his history students, for, unlike many instructors, he did not deliver boring lectures. Walz instead experimented with various media of the time—records, movies, and film slides—to bring history alive in the classroom.

Like many SSC teachers in the 1950s, Walz was strict about class attendance. He followed college policy to the letter. Three unexcused absences and you were out of his class. One of the college athletes, apparently not believing Walz’s warning at the start of the semester, “cut” class a fourth time but thereafter never missed classes. Dr. Walz said nothing, for he had already explained the rules once. Once was enough. When the student showed up to take the final exam, Dr. Walz explained that he was ineligible to take it since he had four unexcused absences. The student had to retake Dr. Walz’s class that summer to obtain his history hours. For most students, especially those who tried their best, Dr. Walz was noted for giving compliments, stopping students after class to say, “Thank you for studying so hard.”

Dr. Walz was among several SSC professors who encouraged the best students to go on to graduate or professional schools. Outstanding SSC students increasingly pursued postgraduate studies in law, medicine, and the various academic disciplines. Students in accounting, history, English, speech, political science, and agriculture received assistantships. The largest number were probably “Mr. [Orval] Childs’ boys” from the farm. He led his students, most of whom worked on the campus farm, with an “iron hand,” but they were inspired by his tough regime and responded with high achievement. From the years 1951–54, thirteen of his former students, who could complete only two years of their agriculture degrees at SSC, went on to finish bachelor, master and doctoral degrees elsewhere.