(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 194, 199-202, 209-211)

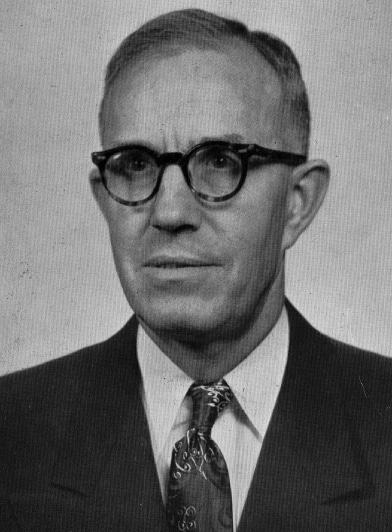

When Colonel Wilkins suddenly resigned as president of Magnolia A&M in mid-1950 to join Lawton Oil Company, the board of trustees selected Dean Graham as interim president while members searched for a replacement and later named Dr. Dolph Camp the new president. In the selection process, the board was no longer limited by the provision of Act 100 of 1909 that required the school’s head to have graduated from an agricultural college. Act 298 (1949) eliminated that restriction on the four district colleges. The SSC board first offered the presidency to Timothy M. Stinnett, a prominent Arkansas schoolman, then serving with the National Education Association in Washington, D.C. When he declined, the board turned to Camp despite Colonel Wilkins’s warning that Camp was not the man for the school’s “big problem—a financial one.” Camp took over the presidency on September 1, 1950. Camp told the board in response to Wilkins’s criticism, “I disagree with Colonel Wilkins that the main job of a college president is finance. I think his main job is education.”

A quiet, soft-spoken man, Camp was an academician at heart. A 1920 TDAS graduate and native of Columbia County, he had served as both teacher and administrator in Arkansas’s public schools. He had been a faculty member at Galloway College in Searcy, a private women’s college later merged with Hendrix College, the Methodist school at Conway. He earned an Ed.D. in educational psychology from New York’s Syracuse University. He served in the Arkansas Department of Education and created a guidance program in the state’s schools. His efforts gained national recognition, and he served as president of the National Association of Guidance Supervisors. His reputation was such that he was invited in 1954 to give guest lectures at Reading University in England. Camp’s administrative style as SSC president was consultative and collegial. He relied upon regular administrative council meetings and invited greater faculty participation in college governance. A larger faculty role was among the many changes necessary to secure SSC’s accreditation by the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools (NCA).

The most urgent requirement that demanded Dr. Camp’s attention was construction of a new library and a larger collection of books and other materials. SSC’s budget request to the legislature in 1951 included funding for a library, but that failed. As a result, Dr. Camp had no choice but to ask the board of trustees’ approval in May for a $232,000 bond issue. By September 1952, a new two-story library of colonial Georgian architectural style (matching Overstreet Hall) opened. The new library was later named for James M. Peace, the school’s first librarian. Located on the east side of campus beside the Greek Theater, the library was the school’s first air-conditioned building. It was designed to hold a maximum of 60,000 volumes in open stacks. SSC’s collection doubled in size over three years when Dr. Camp increased the library budget by some 60 percent. Head librarian Georgina Wright and her successor, Velma Lee Adams, worked very hard to build the collection to 22,673 volumes. That was still well below the size that the American Library Association recommended for small colleges, but it was sufficient in 1955 to win approval during the second NCA accreditation review.

More and better-qualified faculty were required to handle the much-expanded curriculum and degree programs of a four-year college. From 1950 to 1954, the faculty doubled from thirty teachers to sixty. To improve accreditation prospects, faculty with the most advanced degree—the doctorate—were sought. By 1953–54, SSC had sixteen individuals with a Ph.D. or an Ed.D. (22 percent of the total). Five years after accreditation, however, that number fell by half, due largely to the school’s continuing financial problems.

Most of the Ph.D.s hired in the 1950s did not stay long, but a few formed the core of SSC’s senior faculty for decades. They included Dr. Dean C. Andrew, counseling and academic dean; Dr. John Chapman, geology; Dr. Frank Irwin, education; and Dr. Robert Walz, history. Other faculty from the 1950s in that core, several of whom later earned the doctoral degree, included Louis Blanchard, accounting; Betty Blue, Spanish; Ivan Brown, engineering; Robert Campbell, music; Thomas Cleek, math; Avalee Cox, biology; Howard Farris, art; Leon Hardin, education; George and Margie Harrod, counseling and dean of women; Katie Grant Marshall, physical education; Ronald McGee, physics; Delwin Ross, physical education; Richard Samuel, business; and John Smart, chemistry. Staff members first employed in the 1950s who formed another core included Margaret Atchison, business office; Maxine Pyle Porterfield, secretary and registrar’s office; Helen Samuel, post office and secretary; James Smyth, registrar’s office; and Clyde Thomas and Mrs. Everett Young, bookstore.

Faculty with doctorates were needed especially as chairmen of the four-year school’s new academic units—divisions—broad curricular organizations that administered groups of academic disciplines. There were six divisions: Business and Commerce, Education, Fine Arts, Humanities, Natural Sciences, and Social Sciences. These divisions offered seventeen programs leading to the bachelor’s degree. There were also twelve two-year pre-professional programs and three two-year terminal courses of study.

SSC’s initial bid in 1952–53 for accreditation failed despite these positive changes in curriculum, faculty, library, and administrative organization. Part of the reason for the failure was that North Central was in a transitional period, changing standards and methods of assessing institutions. In March 1953, only six of twenty-two colleges seeking accreditation were approved. SSC undoubtedly also needed more improvement. The two-man NCA inspection team from the University of Illinois and Kansas State Teachers College who visited SSC had pointed to several weaknesses needing correction: low faculty salaries, inadequate library resources, lack of faculty publications and experience, insufficient testing to determine teacher effectiveness, unclear distinctions between administration and faculty responsibilities, and questionable athletic scholarships.

SSC’s response to the disappointing review and rejection by NCA was to redouble efforts and to begin in late 1953 a new NCA accreditation process. SSC was one of the first schools to undertake the new process of a comprehensive self-study conducted by faculty committees. The effort was to be headed by the newly appointed academic dean Robert Kibbee. Dean Graham voluntarily handed over his academic position, but he remained SSC’s vice president. For the next fifteen months, Kibbee and the committees put in much overtime preparing the self-study.

• • • • • • • •

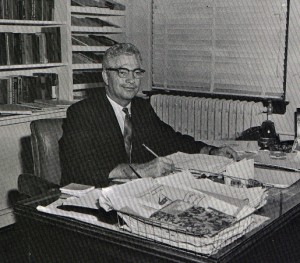

At Magnolia, [Hollywood character actor] Guy Kibbee’s twenty-nine-year-old son, working on his doctoral degree from the University of Chicago, had a more difficult task and no Hollywood fairytale script to save the day. His challenge was to turn a two-year junior college into an accredited four-year institution. First named the senior college’s director in 1951, Robert Kibbee was elevated in late 1953 to academic dean after SSC’s initial accreditation bid failed. He then led a successful second effort. One of his faculty members later declared that Kibbee was “one of the most capable people that ever worked on the school’s campus.” Kibbee ascended the academic ladder after leaving SSC. He concluded his career as chancellor of the City University of New York, the nation’s largest urban system of higher education. While serving in that position, he made a sentimental trip back to SSC and delivered the school’s May 1974 commencement address.

• • • • • • • •

SSC’s second bid to gain NCA accreditation in 1954–55 was aided serendipitously by the Ford Foundation’s funding of the Arkansas Experiment in Teacher Education. The foundation’s Fund for the Advancement of Education selected the state in 1951–52 for a multiyear $3 million grant to promote a new five-year teacher’s degree program. It would include four years enrolled in general education liberal arts courses and a disciplinary specialty and a fifth year devoted to professional education courses and student teaching. In the end, the foundation’s ultimate goal of changing the traditional four-year BSE degree failed due to the resistance of college departments of education. Nevertheless, the Arkansas Experiment improved general education programs in fifteen Arkansas institutions of higher education, both private and public. The colleges were also able to hire more and better-qualified faculty during an era of inadequate funding from the Arkansas legislature. These successes of the Arkansas Experiment were crucial to SSC’s second accreditation effort. SSC received some $212,687 over six years, the largest amount awarded any institution other than the University of Arkansas. Dr. Camp was able to hire twenty faculty with these funds. At the most critical time in the NCA process, this “extra” financing employed thirteen faculty, ten of whom had Ph.D.’s.

The hard work of Dean Kibbee and his thirteen faculty committees supported by Dr. Camp’s creative financing secured NCA accreditation in 1955. Although the second review criticized the college for too few doctorates among the faculty, insufficient scholarly research and publication, a lack of sabbaticals for faculty, and inadequate student financial aid, the NCA report overall was an endorsement of the college. On March 25, at its annual Chicago convention, the North Central Association accorded SSC its seal of approval. Dean Kibbee’s task was finally completed, and he left SSC at the end of the 1955 spring semester. Dean Graham served once again as academic dean until 1957 when Dr. Andrew became dean.