(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 293- 294, 296-298, 300-304, 325)

Of the three vice presidents, [Dr. Robert] Pearce had the most assertive personality, and [SAU President] Dr. [Harold T.] Brinson gave him a wide range of responsibilities. “He was somebody that I could trust and didn’t have to worry about,” Brinson later recalled, even if there was sometimes “friction around him.”

Dr. Pearce’s principal responsibility was the budget, which together with enrollment, was a continuing problem. He initiated the budget system’s computerization to more closely monitor costs. The year before Pearce came, Dr. [Harold T.] Brinson in 1977 responding to student complaints and seeking possible savings had privatized the cafeteria, awarding a contract to Professional Food Management, the first of many food vendors used over the next three decades. To save more money, Pearce secured a board of trustees’ decision to close the school’s print shop and to bid out printing to private companies. He replaced the large Xerox copier in the copying-communication center that Jimmie Watson ran for more than two decades with a cheaper Savin machine, which saved money but caused more glitches for her operation. Pearce supported Physical Plant Director Billy Machen’s successful proposal to install an automated energy savings system in campus buildings. Pearce lobbied successfully in Little Rock over several years to modify the state funding formula to the advantage of SAU.

Planning was seen as one way to manage economic stresses. Comprehensive five-year plans for “management by measurement” were spreading across the academic world as it adopted practices originating in business. Math Professor Raymond Cammack, part-time Title III coordinator, secured a 1979 federal grant for materials from the Higher Education Management Institute (HEMI) to begin a planning process. Roger Giles came to SAU in 1986 as the school’s second director of planning and personnel. Initial efforts produced a mission statement and a set of goals. As a final step in the planning process, an analytical studies team composed of four faculty, three administrators, and two students critiqued the plan.

· · · · · · · ·

Eleven generous alumni and friends of the university paid for the [Historic Granite] Cube [in the new Overstreet Hall plaza], the product of Dr. Brinson’s increased emphasis upon private fund-raising.

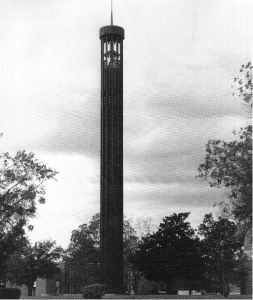

Dr. Brinson had already raised funds to turn the water tower into a statelier monument with carillon bells at its top. Students, faculty, and staff had enjoyed such success telephoning alumni for pledges in the initial October 1978 phonathon that it became an annual event. In 1980, a fourteen-bell set, the largest of which weighed 475 pounds, was ordered from the Paccard Fonderie de Cloches in the ancient French city of Annecy. SAU became one of only a few small state schools with genuine bell chimes and the only one in Arkansas. Computerized controls rang the bells in Westminster chimes every quarter hour. French Professor Gisele F. Souter spoke at the dedication in September about the important role bells had played in communities through the ages and recalled bells pealing in her native village in Brittany.

· · · · · · · ·

The greatest achievement during Dr. Brinson’s fifteen years as president was the dramatic growth in endowments. An independent Southern Arkansas University Foundation was established on December 4, 1980, with a fourteen-member board that elected Herbert Russell as chair and Cameron Dodson as vice chair. [Former President] Dr. [Imon E.] Bruce, who had remained at SAU since retirement to work part-time on fund-raising, was named executive director. SAU, like all of Arkansas’s public universities, sought additional private donations to supplement state funding.

A Diamond Jubilee campaign was launched in September 1982 to raise two million dollars by the school’s seventy-fifth year. Faculty and staff kicked off the drive with nearly 100 percent participation. The campaign’s first year was marred somewhat when Dr. Bruce, feeling he no longer enjoyed Dr. Brinson’s confidence, felt compelled to resign. He did so quietly, but nonetheless rumors spread among his friends to the detriment of Dr. Brinson’s reputation. The Diamond Jubilee itself was a huge success. The number of fully endowed scholarships grew from 78 to 149 and partially funded ones from 59 to 146.

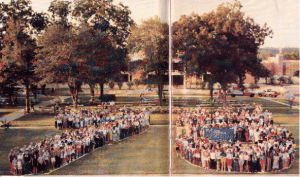

SAU celebrated its seventy-fifth anniversary with a birthday party on the mall on August 31, 1984. A huge cake, six by three feet large, decorated with an icing of seventy-five golden roses and blue trim, fed the hundreds who gathered. The attendees later assembled and formed the numeral seventy-five for an aerial photo. Later that year at homecoming, a bronze plaque honoring the school’s founders was placed at the Bell Tower’s base, and a time capsule was buried. Dr. Robert Walz and Dr. Dan Skelton helped the Mulerider yearbook produce an album of photos and articles to recall the school’s early days.

Fund-raising by the energetic Sharon Eichenberger, who succeeded Dr. Bruce as director of the development office, and by SAU Foundation board members produced steady growth. Pat Weaver moved from her position as dean of women to full-time director of the alumni association and organized numerous meetings and chapters of former students who gave generously. By 1991, the SAU Foundation had grown to more than $6 million and supported 450 named endowments including both scholarships for students and academic enrichment endowments for various departments. As a result, SAU’s endowment ranked third among 152 similarly categorized universities in the United States.

Support from the region was generous. Dean of Business David Rankin persuaded Charles H. Murphy Jr., who headed the El Dorado–based Murphy Oil Corporation, to fund an annual lecture. Professor Ezra Solomon of Stanford University, a former member of the President Richard Nixon’s Council of Economic Advisers, was the inaugural Murphy Lecturer in 1980. He was followed over the years by some of the nation’s best-known business analysts including Jane Bryant Quinn and Lou Dobbs. Dr. Rankin was named in 1987 to SAU’s first endowed professorship, the J. G. Puterbaugh Professorship in Free Enterprise, established with a $100,000 donation secured by business dean Dr. Gayle White from the Puterbaugh Foundation. It honored the founder of McAlester Fuel Corporation, which had led Magnolia’s oil boom that began in the late 1930s.

· · · · · · · ·

SAU funding benefited significantly from [Arkansas Governor Bill] Clinton’s re-election in 1982. Defeated after his first term, 1979–81, Clinton had staged a comeback and increasingly focused on becoming the “education governor.” He brought a “blue ribbon” campaign for educational reform in September 1983 to SAU and spoke on the mall to a large crowd wearing blue ribbons in support. Earlier that spring, a U.S. Department of Education report, A Nation at Risk, had shocked the country with revelations of public schools’ deficiencies. Clinton applied to his native state its message that poor education placed in peril the nation’s economic future. To improve Arkansas schools, he launched a campaign for a state sales tax increase of one cent for K-12 public schools. In exchange for the first major tax increase since 1971, he offered taxpayers new and stronger educational standards and reforms to lift Arkansas’s schools out of last place among the fifty states. Clinton also promised to aid higher education with higher severance and corporate income taxes. He told his SAU audience that K-12 schools would receive 72 percent of the new revenues, and higher education, 22 percent.

Unfortunately, this boom was soon followed by bust. Governor Clinton’s budget in the 1985 legislative session provided SAU another 10 percent increase, but it proved impossible to fund. The years 1985–87 produced the smallest growth in state revenues in twenty years. To avoid an unconstitutional budget deficit, the state finance department made eight funding cuts over two years. When the 1987 legislature failed to restore higher education’s losses, university presidents declared that session the “worst” ever. Even after a freeze on hiring, unfilled positions, and cuts in travel, supplies, and services, SAU had to dip into reserves (savings) in 1986 and 1987 to make up budget deficits. At the downturn’s low point, Dr. Brinson asked the analytical studies team to study the issue of financial exigency (financial crisis allowing dismissal of tenured professors). The study, named PAAR (Programs, Activities, and Resources Review), in the end remained an incomplete document because of difficulties in determining exactly when a financial exigency should be declared and whether professors in departments that might be eliminated held tenure in the university or only in their respective departments. Nonetheless, the board of trustees did approve the incomplete PARR report’s list of priorities in budget reductions in case of financial exigency. Fortunately, state revenues had begun to improve, and PARR could be shelved.

Dr. Paul Marion, director of the Arkansas Department of Higher Education, had to admit that higher education’s earlier gains had virtually disappeared. When adjusted for inflation, he said, state revenues for the universities in 1986–87 were about the same as in 1973–74, and students had to pay more for their education. This was the beginning of an important shift from state-supported to tuition-funded higher education, a trend that would increase in coming decades. The state provided 77.2 percent of college and university revenues in 1978–79, but that amount had dropped to 69.2 percent by 1986–87. Tuition as a percentage of university revenues moved in the opposite direction from 16.1 percent to 23.2 percent. In the same period, Arkansas’s overall university enrollments grew more than 10 percent. Institutions could educate a larger number with proportionately less state support only by charging students more.

In responding to economic difficulties, Dr. Brinson, like Dr. Bruce, used natural attrition from retirements and resignations to manage salary costs, the single largest budget item. Faculty assisted by flexibly teaching in related fields and working part-time in administration

· · · · · · · ·

Dr. Dan England, professor of Biology and chair of the Faculty Affairs Committee (Click photo to enlarge)

Despite uncertain finances, SAU was over time able to increase faculty salaries to levels exceeding those of comparable Arkansas schools. When Dr. Brinson took office in 1976, salaries were behind state universities’ at Monticello, Arkadelphia, Pine Bluff, and Russellville. With Dr. Pearce’s able budget work, SAU’s average moved slightly ahead of them. By 1990–91, that average was even ahead of inflation. Adjusted for inflation, 1990–91 salaries had slightly more purchasing power than those of 1966–67. Like the rest of America in this era, faculty families moved ahead because spouses went to work as never before. Arkansas faculty salaries, however, remained well behind regional and national averages. Dr. Brinson was more receptive than Dr. Bruce had been to faculty involvement in salary matters. He and Dr. Pearce participated in faculty forums on salaries and invited Faculty Affairs Committee chair, Dr. Dan England, and his successors to take part in budget committee preparations.

· · · · · · · ·

Students as well as faculty were hard-pressed through much of this era. In the mid-1970s, 75 percent of student aid was in the form of grants, but within ten years that dropped to 29 percent while a reverse proportion occurred in the amount available in loans. SAU’s student population had one of the state universities’ highest percentages in need of aid. In 1981–82, for example, about 1,500 students received assistance in scholarships, grants, work-study, or loans. In 1991–92, some 80 percent got assistance. Dorothy “Dot” Duncan, who succeeded Auburn Smith as financial aid director, tried not to turn away a student seeking assistance.24

One of Dr. Brinson’s major goals was to keep SAU tuition the lowest in the state. This policy was a long-standing one with roots deep in the institution’s early history. In an era of economic difficulty and marginal enrollment growth, the policy also seemed prudent. Students who could not afford higher tuition rates would stay home and lower SAU’s overall income. The average tuition increase during the 1980s at public four-year schools in the United States was 100 percent. At SAU, it was held to 59 percent. The state legislature forced SAU tuition increases after 1989 by requiring the Department of Higher Education to set minimum levels; schools not using the minimum faced a penalty in budget recommendations. By 1991, full-time students would spend during a year at SAU, still the least expensive state university, a minimum of $4,670 (tuition and fees, $1,170; room and board, $2,100; books, $50; and personal needs, $900). Of course, an uncertain trade-off in lower tuition rates was potentially lost income the school needed for improvements. Tuition choices always involved such calculations.

· · · · · · ·

The great expectations raised by the Good Suit Club’s promise to back new taxes were dashed when Clinton failed to persuade the 1989 regular legislative session to approve them. In a successful effort to secure votes for taxes in the House of Representatives, Clinton threw his support behind a bill to begin a four-year program at Westark Community College. The step would lead eventually to the added expense of yet another state institution of higher education. This transformation was completed in 2002 when Westark merged with the University of Arkansas to become UA at Fort Smith, despite language in the 1964 Arkansas constitutional amendment establishing community colleges that forbade their ever becoming four-year schools. In the 1989 legislative session, Clinton was unable to make enough political deals in the Senate to secure passage of the tax. The resulting minimal increases for the universities produced by that session did not even match the year’s rate of inflation. Every university in the state except SAU raised tuition for the 1989 fall semester. Dr. Brinson refused to follow the pack and cut budgets. Finally, he was compelled to ask the board for higher tuition in spring 1990.