(Excerpted from James F. Willis, Southern Arkansas University: The Mulerider School’s Centennial History, 1909-2009, pp. 145-49)

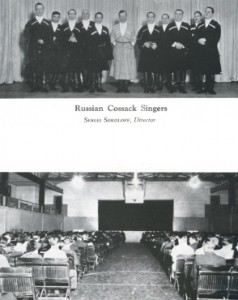

Other activities flourished throughout the 1930s. The lyceum series of speakers and musicians continued every year, usually one per month. A Dallas agency that served most colleges in the southwest booked the acts. As a result, many of the events appearing at larger schools also came to Magnolia. Russian entertainers were most often on the playbill, artists who had fled the Communist revolution. Among those appearing on the armory’s stage were the Russian Cossack Chorus, the Royal Russian Chorus, and the Russian Marionette Theater. A famous opera star, Mary McCormic, a native Arkansan who had sung with the Paris National Opera, gave a concert. Another kind of entertainment was provided by a famous travel lecturer, Jim Wilson, whose motorcycle trip across Africa had been featured in National Geographic.

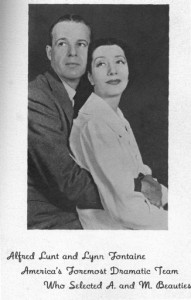

Faculty sometimes took students to Little Rock or Shreveport to see famous productions like the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontaine in Robert Sherwood’s Pulitzer prize–winning play There Shall Be No Night, and Katharine Hepburn in the touring Broadway play The Philadelphia Story. Twenty-six members of Jewell Stevens’s Stagecrafters Club waited at the stage door of Robinson Auditorium in Little Rock to secure Hepburn’s autograph on their programs.

The Mulerider yearbook editors, like those of many colleges, used celebrities to choose campus beauties for each year’s annual. The staff would send photographs of twenty coeds to Hollywood stars including native Arkansans like Dick Powell and Lum and Abner who would select one as the winner and four more as maids. Publicity agents no doubt made the actual pick, but personalized letters communicating results were reprinted in the yearbooks and made it appear the famous entertainers had agonized over their choices. The Mulerider staff annually held a “Stunt Night” to raise funds, an affair at the armory where campus clubs competed in skits or other entertainments (stunts) to win a free page in the yearbook. The evening’s climax was announcement of names of beauties the stars had selected. Students entertained themselves at these kinds of gatherings. Imitating a popular radio program, Major Bowes Amateur Hour, students staged a similar competition in October 1937 that Sue DeLaughter won over fifteen other entries with her impersonation of famous movie stars ZaSu Pitts, Mae West, and Greta Garbo.

The old literary societies of TDAS disappeared in the late 1920s. At many schools, such organizations evolved into or were replaced by fraternities and sororities. That did not happen at Magnolia A&M. Its students were on the whole too poor to afford the expense of such social organizations. The Arkansas legislature in 1929 replaced an earlier ban on fraternities with a new prohibition that exempted colleges and the university. Many people, however, continued to view these groups as undemocratic because they were not equally open to all students. Faculty would not have wished to exacerbate an already existing class and residential divide among A&M urban and rural students. Day students from Magnolia sometimes teased campus residents, calling the school a cow college. Roger Louis Wilson, class of 1933, later explained this campus division, “You were either a country boy or you were a town boy. They didn’t mix too good.” Overstreet in the early 1930s tried to preserve the debating function of the literary societies. He held an “Open Forum” every Thursday night inviting students, faculty, and local citizens to debate current issues and controversies. The Open Forum disappeared from lack of interest and because a debating club was established to participate in intercollegiate competition. A&M’s team won the 1932 Arkansas Junior College Forensic League championship.

Religious organizations, particularly the YMCA and YWCA, remained among the most active and popular clubs. Their projects included decorating the Lone Pine Tree with Christmas lights each year. Sponsor Merritt Alcorn took students to state and national meetings of YMCA. Local churches began using buses to ferry students to worship on Sundays. Fewer ministers were invited to the school. The board ruled against allowing a Baptist congregation to erect a building on campus, accepting the argument that such an arrangement would be an unconstitutional violation of church-state separation. The college glee club and its musicians, on the other hand, twice collaborated with local churches to produce Handel’s Messiah at the armory.

The college was slow in setting up honor societies to recognize student achievement. The Stagecrafters in 1936 established a chapter of Delta Psi Omega, national honor society in college dramatics. The principal academic honor society of junior colleges, Phi Theta Kappa, did not, however, take its place among A&M organizations until 1939 when the Gamma Omega chapter was established. Only arts and science majors whose academic performance ranked in the upper 10 percent of the student body were eligible for membership. The chapter was inaugurated on November 25, 1939, with five charter members. Marcellus McCrary was its president, and English instructor Inez Couch served as sponsor. At graduation, the W. R. Cross Award was presented to the “best student citizen” at A&M. Robert Walz, who edited both the Bray and the Mulerider while also working at the bookstore in 1938–39, received the prize that year.

Theater and musical organizations and the college band were possibly the most active of all groups. In addition to performing on campus, students appeared frequently on live radio broadcasts from El Dorado, Shreveport, and Little Rock. Lloyd. E. Crumpler directed the college band in the early 1930s. From 1935 to the end of the decade, Jimmie Justiss, who had graduated in 1931, led the band. When funds ran low, Elizabeth McMorella became its sponsor and raised money to purchase instruments. A striking woman of dignified bearing, she became so enthused with her latest volunteer project that she often accompanied the band on its off-campus trips wearing a gorgeous custom-made cape of blue and gold school colors. On one occasion in 1936, she treated band members to a banquet on the roof of the Youree Hotel in Shreveport and paid the cover charges so they could attend its dance featuring the orchestra of Duke Ellington. French instructor Charles Haydon organized nine of the most talented band members in 1936 into a dance band named the Varsitonians. They performed for campus events and earned much-needed money while providing the music for local dances. Haydon, who led European trips each summer for a Dallas tourist agency, arranged for two of the Varsitonians—Walter Whitlow and Sidney Smith—to play with the orchestra aboard the great French liner Normandie on one of its transatlantic voyage in 1938.

Varsitonians in 1938. Front, l. to r.: Albert Prator, Roy Lewis, Sidney Smith, J. W. Gladney, and Bob James. Back, l. to r.: Billy Bennett, Henry Mize, Walter Stokes, James Van Sweden. Director: C. E. Haydon, French instructor (Click photo to enlarge)

Throughout the depression era, many citizens of Magnolia hoped that oil wealth found earlier in Union County bringing wealth to El Dorado would be discovered in Columbia County. Hope for the future got a boost in 1937. The Schuler well came in near the Columbia County line, and Postmaster General James A. Farley traveled from Washington, D.C., to dedicate Magnolia’s new post office. The city’s largest celebration up to that time greeted him with a huge parade and a feast at the courthouse square that fed thousands. When it came time to dedicate the post office, Farley was much amused to participate in a christening ceremony using a bottle of Magnolia Belle’s milk rather than the traditional magnum of champagne.

Finally in March 1938, after twenty years of dreaming and drilling, a huge oil strike was made near the city when the Barnett No. 1 well blew in at a depth of more than seven thousand feet. Soon the local “telephone exchange looked (and acted) like a madhouse” as news spread across the nation. By year’s end, there were scores of producing wells. Business boomed as new residents rushed to Magnolia.

To celebrate oil and returning prosperity, Magnolia’s leaders staged an Oil Jubilee on March 5, 1940. Every business, civic club, and the college entered floats in a long parade. Governor Carl Bailey attended and crowned the Queen of Petroleum, an A&M sophomore, Ferol Dumas from Walkerville. She became the first girl from South Arkansas to represent the state in the Miss America pageant competing at Atlantic City, New Jersey, in September 1941.