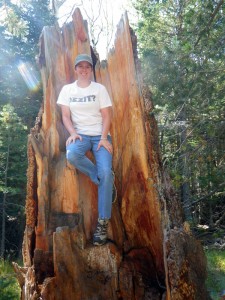

In August 2012, SAU junior Deana Hughes set out for a Grand Canyon Honors Semester in Arizona as a biology major, but she returned with professional experience, a new focus and degree plan – wildlife conservation.

In August 2012, SAU junior Deana Hughes set out for a Grand Canyon Honors Semester in Arizona as a biology major, but she returned with professional experience, a new focus and degree plan – wildlife conservation.

Hughes realized her professional calling during her fall semester working with professors and national wildlife conservation experts in the Grand Canyon. For someone who had never left her home state for an extended period of time, the four-month experience studying at Northern Arizona University (NAU), which has a larger student population than the entire population of Magnolia, was life changing and eye opening. It was quite a different landscape from the heavily wooded lands of her Arkansas home.

“On the trip out there, through New Mexico, there weren’t many trees,” she said. “My biggest fear was that I would spend my semester in a place where trees only come about knee high.”

As Mother Nature would have it, the sprawling campus in Flagstaff is located at the base of Arizona’s highest point, Humphrey’s Peak, which is dotted with an ample variety of trees, from big spruce and fir trees to ponderosa pines and quaking aspens. Her class schedule was vigorous and weekends were filled with field trips and excursions. Every Wednesday and many Saturdays were spent an hour and a half away from the campus on the southern rim of the Grand Canyon doing research on the non-native elk encroaching into the region.

Hughes chose her research topic her first week at the Grand Canyon after networking with Cory Mosby, a wildlife biologist at the South Rim.

“They have a big issue with elk over population out there,” Hughes explained.

The southwestern United States, including Arizona, was once filled with a native species of the animal known as Merriam’s elk. They became extinct. Rocky Mountain elk from Yellowstone National Park were relocated to two sites in Arizona, which reestablished the herds in the state for big game hunting. According to Hughes, the relocated elk had lost their only natural predators when wolf populations were greatly diminished in the 1990s and the elk multiplied, threatening natural resources for other native wildlife.

“Cougars and coyotes are predators found in Arizona, but elk are so big that it takes a pack of animals to take them down. Cougars and coyotes don’t hunt in packs and wolves are no longer found in Arizona. It allows the elk herds to flourish,” she said. “Grand Canyon National Park was becoming concerned that the elk populations were competing with the native mule deer population.”

Another concern is the violent nature of elk during rutting season and their increased presence in areas where humans gather. In Arizona, water is so scarce that they manage their water resources very tightly and practice water reclamation. The elk have learned to use the water reclamation ponds to their advantage. Even the public water bottle fountains create more interactions between them and people.

“Their numbers have increased exponentially in the region since they were reintroduced to Arizona,” said Hughes. “But not inside the national park.”

Hughes’ research will be used to develop an elk management plan for the park. Her recommendation was to diminish things that draw elk near public spaces, where they create dangers and literally create traffic jams (called elk jams) where they have been known to attack people or damage vehicles.

“They are mainly grass grazers,” said Hughes. “Since there is no hunting in the national park, there is no way to cull the herds. My advice was to replace the green lawns around the hotels and visitors’ centers with natural desert landscaping that doesn’t attract them and to change the water fountains to spigots they cannot use.”

Hughes could easily talk for hours on the topic of her research and her experience. Her most memorable experience was the white-water rafting trip on the Colorado River that put her face to face with fears of rapids and forces of nature out of her control.

“The most valuable part of the experience was I learned that I can do it,” said Hughes. “There is no way to go down the river without being affected. The river teaches you things about yourself that you don’t realize – things you don’t necessarily want to learn. I still have that fear, but I know I can survive it. I did it once. It’s done. I know what I am capable of.”

She walked away from her honors semester with 16 hours toward her degree and a clearer path for a future in conservation. She changed perceptions about her home state and made life-long friendships in the process.

“I had a close friend throughout my life. Now, I have 12,” she said, of the bonds she made during her semester in Arizona. “They told me that I had blown the stereo type they had of an Arkansan completely out of the water. I was the most social networking savvy among them. I was the one who set up a web cam and a Ustream account to broadcast our symposium I maintained their official Facebook page. I had a few who said they never wanted to visit Arkansas, until they met me.”

Hughes said she looks forward to meeting up with her honors semester friends at the 2013 National Collegiate Honors Council conference in New Orleans next November and hopefully in five years reunite with them in the bottom of the Grand Canyon.